Africa’s leaders: psychology matters

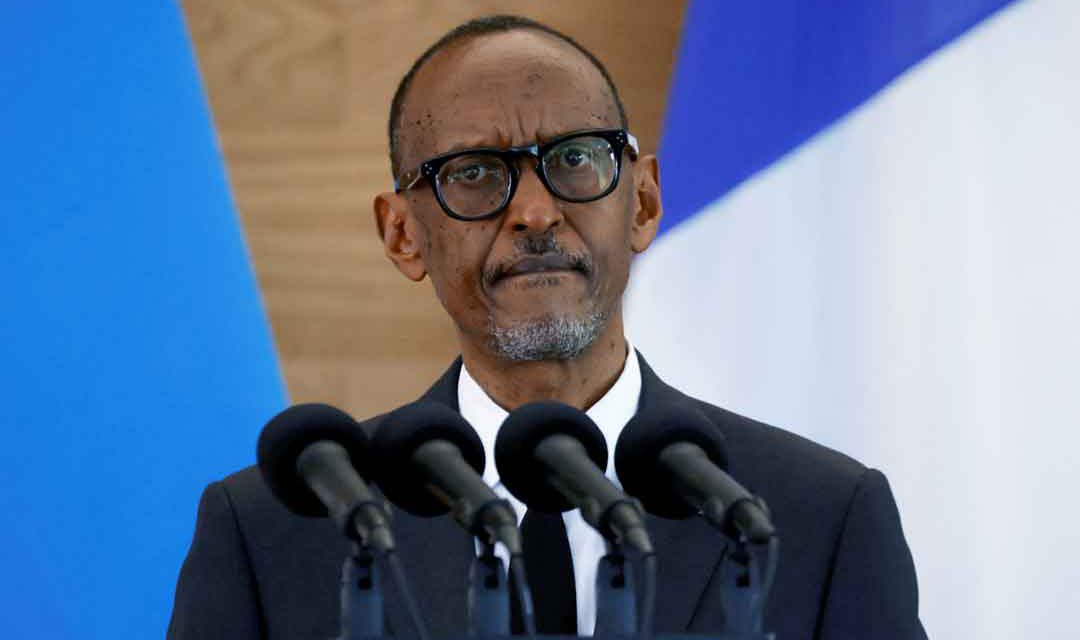

Rwanda’s president, Paul Kagame Photo: Wikimedia, Copyright World Economic Forum www.weforum.org / Eric Miller emiller@iafrica.com

By Francois Misser

“Africa doesn’t need strongmen. It needs strong institutions,” said former US president Barack Obama during a visit to Ghana in July 2009. Yet the work of building strong institutions is not easy on a continent where the weakness of institutions strengthens the role of all too many so-called “providential leaders”.

One didn’t necessarily have to physically meet with former Zairian ruler Mobutu Sese Seko, for instance, to feel his presence from miles away – and the fear which it inspired. In September 1981, I was on board a steamer sailing up the Congo River. Suddenly, the Belgian captain ordered the ship’s engines to stop. The river traffic was paralysed for two hours – steamers, pirogues and barge-pushers alike. The captain and the crew became increasingly tense, nervous and silent, until the “Supreme Guide”’s riverboat, the Kamanyola, appeared – complete with a helicopter on the rear deck. The relief when it disappeared was palpable. Once again, laughter was heard on the river.

At that time, even Mobutu’s staunchest critics accorded him extraordinary influence. Former Zairian prime minister Jean Nguza Karl-i-Bond once described him as the “incarnation of Zairian evil”. In the country that he dominated, Mobutu was everything, the alpha and the omega, the beginning and the end. People believed that the “Great Leopard” was endowed with superpowers. Many Zairians believed that his superpowers had allowed him to escape death at the battle of Kamanyola by protecting him against bullets.

Those were times of giant figures, when the destiny of a nation could depend entirely on one man. I never felt this more strongly than in Angola, with regard to one man – Jonas Savimbi. In August 1990 it was an ordeal to arrive at his headquarters in the “lands of the end of the world”, as the area was called by the Portuguese. A three-hour night flight over Botswana and a two-hour drive on endless dust roads through the bush finally brought me to Jamba, UNITA’s “capital”. It took another week before I could meet o mais velho (the old man) in a vast military camp somewhere near Mavinga.

Everyone in Unitaland felt Savimbi’s presence. Many people in UNITA genuinely believed that he was endowed with magical superpowers. “Even self-confident worldly men trembled in Savimbi’s presence,” the Angolan academic Ricardo Soares de Oliveira writes in his 2015 book on the country. “It is widely acknowledged that the personality and choices of Jonas Savimbi … are more important for understanding UNITA than its loosely defined ideology or formal decision-making structure.”

His talent and charisma were enormous. The man was fluent in Umbundu and Kimbundu, as well as Portuguese, French and English. He delivered long, formidable Castro-like speeches, one of which I witnessed in Jamba during the so-called “last Congress in the Bush”, in March 1991. It was on that occasion that a former South African military officer and diplomat, Sean Cleary, described Savimbi as a Moses who would lead Angolans to the promised land of democracy. Savimbi’s ego had no limits. No dissent was tolerated. Over the years, a number of his deputies – among them UNITA foreign minister Tony da Costa and party general Miguel Nzau Puna, who both left UNITA – either defected or were murdered. This was probably the case with Tito Chigunji, who was UNITA representative in the US when I met him in 1988 and later became foreign secretary of the movement. He was shot in 1991 somewhere in the Angolan bush in obscure circumstances.

Sixteen years after the death of this would-be absolute king, many analysts believe that his ego was the main reason why the Angolan war resumed after the first round of the presidential election in 1992. By comparison, his successor, Isaias Samakuva, was little more than a polite leader of the opposition. Other factors surely also had an influence on UNITA’s capitulation, such as exhaustion, low morale, war fatigue and failing military tactics. But nobody then denied the role of Savimbi’s immense personality.

Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, by contrast, is a very different type of man. I met him for the first time in December 1994, in a suite at the Brussels Hilton, during his first visit to Belgium after the genocide. Extremely tall, in a grey suit and a tie. His voice was soft. Both the smile and the eyes behind the spectacles looked benevolent, perhaps because he had been briefed to talk positively to a French-speaking audience. Hutu extremists had painted a horrendous picture of him. Some media, influenced by Elysée Palace propaganda, had represented him as a Pol Pot of the Great Lakes.

Instead, I found in him someone who understood that the fact that I was French would not automatically mean that I shared the hostile attitude of the then-French government, that there would be a distinction between the attitude of a state and that of an individual citizen. Yet, at the same time, he was, I realised during the first hour of that one-on-one discussion, an iron fist in a velvet glove. He adopted a very directive tone when he received a call from the Rwandan ambassador in Brussels, Denis Polisi – a man who I knew was capable of delivering inflammatory speeches in his deep, low voice, but who was very submissive with the boss.

One month later in Kigali, when I again interviewed Kagame, I was plunged into a totally different atmosphere. His discrete and omnipresent secretary, Emmanuel Ndahiro, kept postponing meetings. When, finally, I got to see him, Kagame was no longer the statesman abroad on a diplomatic tour, but a leader besieged in his ministry of defence office by innumerable challenges, including incursions by genocidaires at the Congolese border and other attempts at destabilisation. Nevertheless, he took the time to offer another version of his story and of Rwanda’s history for consumption to the outside world.

I decided to ask this man, who had been so demonised, who he was and how he had become the man of the moment. The result was included in my book Towards a New Rwanda, an Interview with Paul Kagame, published a year and half after the genocide. His background was similar to that of other leaders of the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), who like him grew up in refugee camps in Uganda. In 1961, when he was four, he and his family barely escaped their home on the hill of Nyarotuvu, in the Gitarama prefecture, during a previous genocidal wave. “[Attackers who] were burning houses, killing people, realised we were going to flee,” he told me. They were lucky to be evacuated. With his family, he became a refugee in Ugandan camps, where conditions were “horrible”, and many Rwandan refugees died of poverty or disease.

There is little doubt that such dire conditions helped to shape the personality of a man who became a guerrilla and then a professional soldier, by necessity rather than by choice. The complete refusal of the Hutu-led government of that time to allow the refugees to return left them with no option other than armed struggle. To make that possible, Uganda would have to be liberated, if it was to offer a springboard for an attack on Rwanda. At the age of 24, with his friend and comrade, Fred Rwigema, Kagame joined a group of 27 fighters led by Yoweri Museveni, who aimed to liberate Uganda from Milton Obote’s dictatorship. At the end of this liberation war, Kagame drew the lesson that Museveni’s victory in 1986 was closely associated with political work and particularly with support from grassroots people, as well as the tactics and strategy employed.

Kagame’s story is therefore one of adaptation to circumstances. It was not by choice that he became the boss of Uganda’s military intelligence, he told me. It was he who urged the first attack by the RPF in October 1990 against the late Juvenal Habyarimana’s supremacist Hutu regime. The attack had to be launched in haste. “Uganda had started becoming uneasy about complaints from Rwanda concerning the presence of refugees on its soil,” Kagame told me. “We had to move fast, before the Ugandan army threw us out.”

The attack was a disaster. The commander in chief, Rwigema, was killed in an ambush on the first day. Three weeks later, on the 23 October, 1990, the interim commanders, Peter Bayingana and Chris Bunyenyezi were killed in separate ambushes. Kagame was called back to the field from the US where he was attending a training course at Fort Leavenworth, Texas, and found “total disorganisation”, as he put it. He ordered a complete reorganisation of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA). This approach, combined with Kagame’s experience of the guerrilla war with the National Resistance Army (NRA), led the RPA to it first military victory in 1993. Shortly after that, the Arusha peace agreement imposed a power-sharing deal on Habyarimana’s party and the opposition, including the RPF.

Kagame, the new commander in chief, led the fight from the field. A fellow soldier, Sergeant Jean Bosco, told me after the fall of Kigali in July 1994 that Kagame was regarded as the best shot, the fittest man – “the best of all of us”. A former Belgian paratrooper, Jacques Collet, told me that Kagame enjoyed enormous admiration from his fellow soldiers. He created a disciplined army that was capable of impressive economy in its use of ammunition and a high degree of accuracy in their deployment, while drinking alcohol was forbidden. By these measures, the strict and austere Kagame compensated for the RPA’s inferiority in numbers and in equipment. A particular quality of his struck me during my interviews with him: he was careful to refer to enemies with respect. He always referred to Habyarimana by his name and never used the many disparaging nicknames by which he was known.

Kagame became a successful leader because he was part of a group with strong social cohesion: during the struggle RPF militants sometimes referred to their organisation as umulihango(family). But to my mind, there is little doubt that his personal qualities contributed to creating that cohesion. At the end of the day, he brought the RPF army insintzi (victory), in July 1994.

There is also little doubt, however, that Kagame’s repression of opponents has been implacable. Many civilians were massacred during his campaign against the genocidaires in the DRC in 1997 and during the 1998-2003 war in the Congo. There are also suspicions about the deaths of opponents abroad. Former Rwandan Minister of the Interior and RPF member Seth Sendashonga was shot dead in his car in a Nairobi street by two unidentified gunmen on 16 May, 1988. Former director general of the Rwandan defence forces, Colonel Patrick Karegeya, was found dead in his hotel room in Johannesburg on 1 January, 2014. In both cases, friends and relatives of the victims accused the Rwandan intelligence of perpetrating the murders.

Yet some 25 years after the genocide, Rwanda has become one of Africa’s most vibrant economies. In 2005, Microsoft Africa’s CEO, Cheick Modibo Diarra, picked Rwanda as a test market for the group’s continental strategy, citing Kagame’s keen interest in e-governance and e-education. The sometime military strategist, tagged the “Bismarck of Africa”, has embarked on a battle for his country’s development, and with some success. By 2015, Rwanda had met almost all of its Millenium Development Goals targets. Kigale, a former war zone, is now celebrated as a buzzing capital.

Psychology matters. For me, another example of this was provided in neighbouring Burundi by Major Pierre Buyoya, whom I also interviewed several times in formal or less formal conditions, the first time in the presidential palace in 1989. I would later meet him at hotels, conference centres and even drink whiskey with him at his Bujumbura home in the posh neighbourhood of Kiriri (Kagame is rather the tea drinker type). Buyoya shared some characteristics with his cold-blooded and implacable predecessor, Colonel Jean-Baptiste Bagaza, whom he toppled in a bloodless coup in 1987. Like Bagaza, Buyoya was born in Burundi’s southern province of Bururi, in the same small town of Rutovu. Both belonged to the Hima Tutsi sub-group and both went to the Brussels Royal Military Academy. Yet their styles and personalities were completely different.

Bagaza, who overthrew his relative, Captain Michel Micombero, in a bloodless coup in 1976, never tolerated the slightest dissent. I met him, after he had been overthrown himself, in a small hotel in Brussels, a bitter and frustrated man. He had spent the previous 11 years repressing the Hutu majority, who were excluded from the army and key administration jobs. When communities with a Roman Catholic base criticised these government policies, Bagaza declared war on the church and began expelling missionaries.

Buyoya was more compromising. After a wave of inter-ethnic violence in August 1988 between members of the Ntega and Marangara groups, he tried to build bridges between Hutus and Tutsis and eventually embarked on a path of political reform and dialogue. His attitude was reminiscent of the character in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel, The Leopard, who says: “if you want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”. Buyoya added to this a touch of Machiavellian wisdom. To keep their privileges, he saw that the Tutsis would have to accept a pluralistic democracy. A Hutu prime minister was installed in October 1988 and again after the elections of 1993. But for the Hutus the accumulated frustrations were great. Rather than supporting Buyoya, they voted for Melchior Ndadaye’s Hutu-led Burundi Democratic Front, which won a landslide victory. Yet, that wasn’t the end of Buyoya’s career.

Evidence of his resilience was provided in 1996, with a coup waged in his favour by the then-defence minister, Colonel Firmin Sinzoyiheba. Buyoya re-emerged as the new president and remained in office until 2003. I remember him as a clever man who spoke softly with a sometimes crooked smile. He was almost predatory, like a cat conscious of its nine lives. I met with him many times between 1989 and 2014. During that time, I encountered a man who was at the top, then a has-been, then a man at the top again. Throughout it all, there was always a sense of seduction about him. I know that former US Assistant State Secretary for African Affairs Herman “Hank” Cohen held him in high esteem. It was not surprising to see Buyoya later embarking on an international career, as an election observer on behalf of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), as peace mission leader in Chad and, lately, as the African Union high representative for Sahel.

If anything demonstrates that personality is an important factor in African political events, it is the fact that close family members may act in totally opposite ways. This is shown by the careers of the late Étienne Tshisekedi wa Mulumba and of his son, Félix, who was sworn in as president of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) on 24 January this year.

Over many decades, Étienne Tshisekedi, with other dissident MPs, was an important figure of resistance against Mobutu’s and Laurent Kabila’s dictatorships and, later, Joseph Kabila’s authoritarian rule. Stubbornness is the quality that comes to mind. I can still see the pictures of his bleeding head after he was beaten by Mobutu’s security, which I published in the French magazine Afrique Asie. Later, Étienne and his family, including the 19-year-old Felix, spent several years under house arrest in a village in Kasai province, without electricity or water. Even so, Étienne Tshisekedi was able to draw large crowds of supporters in Kinshasa, where he was hailed as a Moses who would bring the Congolese flock to the land of democracy.

His son, by contrast, the rather plump “Fatshi”, is a much more easy-going guy – a “good pal”, according to his friends, and so far does not appear to have inherited his father’s fighting spirit. In January 2018, Félix Tshisekedi escaped from a Kinshasa church, where a protest meeting was taking place, as the police were besieging the building. “You are abandoning us,” angry youths shouted in despair. Even before his election, other opposition leaders suspected that he had struck a deal with Joseph Kabila. Former companions in the opposition were not so surprised when the DRC’s independent national electoral commission declared Tshisekedi junior the winner – though even the AU expressed “serious doubts” about the conduct of the election. Now, Félix is mainly thought to be a collaborator with Joseph Kabila’s authoritarian regime. Same blood, different mind, different attitude.

When different leaders are confronted with similar circumstances and sometimes even the same adversary, the outcome of their actions may vary completely. Surely the influence of personality must play a role. We have seen the cases of the guerrilla leaders Savimbi and Kagame and the coup-makers Bagaza and Buyoya. This applies as much to civilian politicians such as the Tshisekedis, father and son. For me, one of the main differences is between those who will risk their lives and those who won’t. Another is the difference between those whose struggle is against injustice and those who are motivated by the opportunities of office or by a wish to retain their privileges – even if the price is oppression.

As a long-time correspondent, I have met and talked with many African leaders and politicians. You learn much from meeting them personally, and for the journalist this is indispensable. But you can also learn a lot from seeing them through the eyes of their supporters. Both Kagame and Savimbi enjoyed the genuine admiration of their followers, and both were cordially hated by their enemies. Yet the essence of Savimbi’s power, like that of Mobuto, was in the fear that he inspired in his subordinates.

Of them all, I would say that the most impressive is Kagame. He doesn’t fish for compliments. He admits freely that he isn’t particularly interested in other leaders. Yet, very pragmatically, he is still prepared to learn from them. As he told me, one can learn even from leaders one doesn’t like.