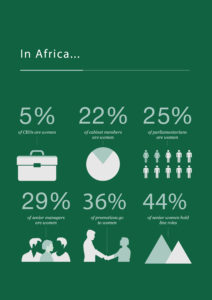

Women make up almost exactly half the population of the region, but you’d never say so based on how few there are in senior management

It is rather surprising that African women, who raise and support future national leaders – and who therefore count among the founders of nations – are seldom allowed to participate fully in the economic and political lives of their nations. Despite the fact that they constitute around half of the population, women are marginalised and disadvantaged in all sectors of the economy, as well as in relation to the development agenda.

All around Africa, governance practices still give little credence to the views of women. In Anglophone West Africa, things are no different. In Ghana, the proportion of female to total board members generally ranged from 7% to 25%, according to a 2016 study by the International Finance Corporation, Gender Diversity in Ghanaian Boardrooms, while the highest number of women on any particular board amounted to a quarter of the total board membership. Some 24.05 % of the sampled boards consisted only of males. In other words, one out of every four boards had no female representation at all.

This skewed situation is not peculiar to Ghana; it is prevalent across West Africa. In Sierra Leone, for example, only 7.9% of firms have a woman among the principal owners, according to a 2015 International Labor Organization (ILO) study, Promoting Jobs, Protecting People. In Gambia, for example, some 16.8% of firms have female participation in ownership, while 12.3% of firms have female majority ownership and 9.6% have a female top manager, according to a 2018 World Bank study.

Why are there so few women in decision-making positions in companies, businesses and institutions in West Africa? Well, for one thing, women’s cultural roles are often defined by outdated ideas that exclude them from decision-making roles in society. These cultural roles are enforced by gendered socialisation, the process by which social expectations and attitudes associated with one’s sex are learned. Gendered socialisation begins at birth, and gendered socialisation continues during adolescence and into adulthood, according to a 2017 discussion paper by UNICEF on adolescent gender socialisation in low- and middle-income countries.

In West Africa, women are seen as homemakers and nurturers who have no place in the world of paid work. Though this view is slowly changing, women working in the formal economy – the public or private sector – are usually relegated to the lower levels of employment, where influential decision-making is non-existent. Thus, women are affected by the decisions of a majority male leadership, while their lack of representation in top-level hierarchies prevents them from having agency and shaping their societies in formal spaces.

At an International Woman’s Day event held in Gambia in 2015, Saiba Suso, a programme officer with Activista Gambia and a lecturer at the development studies unit of the University of Gambia, said African women continue to experience discrimination in many areas such as education, the labour market, religion, job opportunities and decision-making. Her remark was borne out, three years later, by a UN Women 2018 report on the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). “There can be no sustainable development without gender equality,” the report says. Yet in sub-Saharan Africa, women still suffer more poverty than their global counterparts, and more hunger. Women in the region also face higher rates of maternal mortality than the global average, while 48.1% of girls are less likely to learn to read and write at primary school as compared to 43.6% of boys in the same region.

In Ghana, some 61.4% of females interviewed had no formal education compared to 39% of males, according to a 2016 report by the Institute of Economic Affairs in Ghana. After primary school, the proportion of males far exceeded the proportion of females at all levels of educational attainment. Lack of access to education means that women are less employable in formal sectors and they often have to resort to informal jobs, which help to pay the bills but do not contribute to their financial independence.

In Ghana, some 61.4% of females interviewed had no formal education compared to 39% of males, according to a 2016 report by the Institute of Economic Affairs in Ghana. After primary school, the proportion of males far exceeded the proportion of females at all levels of educational attainment. Lack of access to education means that women are less employable in formal sectors and they often have to resort to informal jobs, which help to pay the bills but do not contribute to their financial independence.

In Liberia, more females (4.5%) are unemployed than males (3%), according to a recent (undated) World Bank Institute report, Striving for Business Success: Voices of Liberian Women Entrepreneurs. Most women are self-employed and operate in the informal sector. Some 13.4% of males are employed in the formal sector as compared to 4.5% of females. Female entrepreneurs in Liberia work mainly in the small retail and trade sector, and 60% of women own informal enterprises, as compared to 45% of men, according to a 2012 World Bank report.

In West Africa, as elsewhere on the continent, women also make significant contributions to crop production, animal husbandry and marketing. But this work is unstable, poorly paid and usually invisible, resulting in a high incidence of unemployment among women as compared to men. Globally, the unemployment rate of women for 2018, at 6% – is approximately 0.8 percentage points higher than the rate for men. Altogether, this means that for every 10 men in a job, only six women are in employment. For Africa as a whole, the male employment-to-population ratio was estimated at about 69.2% compared to the female employment-to-population ratio of only 39.2% (Gender Equality in Employment in Africa: Empirical Analysis and Policy Implications, 2014). Women’s lack of access to education means that companies have a smaller pool of developed talent to select from when recruiting for high-level positions in public and private companies and governmental organisations. In West Africa, women face a “glass ceiling”: the higher up the corporate ladder, the fewer women are to be found in senior positions. In her 2013 M Phil thesis on the glass ceiling phenomenon among managerial women in Ghana, Dorcas Gyekye argued that men’s promotion into leadership positions was based on their perceived potential as leaders, while women’s promotion was adjudged on the basis of their perceived performance.

Members of the “old boys’ club” – an informal system through which men use their positions of influence to provide favours and information to other men – will see potential in people they deem to be more like them. So it is that more men are promoted than women. Women who succeed in getting to the top may be there as a form of tokenism – which, in my view, goes some way to accounting for women’s rivalry in such contexts, since surviving can depend on factors other than professional performance. According to the Gender Diversity in Ghanaian Boardrooms report (2018), some 49.37% of the women on company boards were non-executive directors, while only 6.49% of organisations had women as the chair of the board.

Away from the world of employment, whether formal or informal, African women face additional burdens. According to a 2017 report by the UN, women do at least two and a half times more unpaid household and care work than men. Since household work is unpaid, this leaves women with fewer resources and even less time or opportunity than men to focus on career advancement. According to a 2016 report by the IEA in Ghana, women spend most of their time on household activities such as cleaning (94%), cooking (90.2%), water collection (73.8%) and childcare (68.5%), while a significant proportion of men (65.0%) control the household finances.

Worldwide, women are also often paid less than men for the same work, and West Africa is no exception. According to the ILO Global Wage Report 2014/15, women’s average wages were between 4% to 36% less than men’s; and astonishingly, this gap widens in absolute terms for higher-earning women. Similarly, women in 32 African countries were paid less than men for comparable roles. In West Africa, Ghana heads the list: women earn $3,484 per annum as compared to men’s $6,485, according to a 2016 report by the World Economic Forum on the global gender gap. Unequal rates of pay further reduce women’s ability to make investments, support their families, and establish their own financial independence.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that women take less-demanding jobs – to be able to do their unpaid labour. Employers often cite this as a reason to exclude women from decision-making positions, whether public or private, saying that they will have to attend to household tasks and decisions while at work. Contemporary changes at the workplace that are now quite common in the developed world – such as working from home and longer or parental leave – would help to alleviate the strenuous conditions many African women experience. Other social changes, such as sharing household labour, would also help.

The inclusion of women in high-level positions makes economic and social sense. Research has shown that when there is an equitable representation of male and female voices at the higher levels of corporations the results are improved performance, more innovation, an enhanced quality of decision-making, better use of the talent pool, deeper customer intelligence (customers are, after all, both male and female) and an improved quality of corporate governance and ethics in decision-making, according to a 2014 document on achieving gender equality in the workplace by the Australian government’s Gender Equality Agency.

It will be obvious that boards on which there is an under-representation of women will make decisions skewed towards a male point of view. If both sexes are fairly represented, by contrast, there is a much higher likelihood that decisions will be balanced around the views of both men and women. Companies with a more equal distribution of the sexes in the boardroom financially outperform companies with a less representative gender mix, according to a McKinsey and Company’s report, Diversity Matters (2015). In short, globally, women are good for the bottom line. The same will be true of every region in Africa, including our own.