Digital diplomacy has emerged as one of the most topical issues in the post-Covid-19 pandemic period, especially in Africa, where diplomats and government officials have resorted to the use of the internet, social media, and other ancillary digital technologies to circumvent travel and gathering restrictions associated with non-pharmaceutical interventions aimed at curbing the spread of the deadly virus.

The concept of digital diplomacy refers to the broad use of technology, particularly the internet and other information and communication technologies (ICTs)-based innovations, in the conduct of diplomacy. Unlike analogue diplomacy, where diplomats and government officials relied on in-person meetings, verbal and non-verbal cues, signing of physical documents and the exchange of handshakes, modern day diplomacy is increasingly being digitised.

Taking advantage of the technical and social affordances of digital technologies, some diplomats and government officials in Africa are slowly embracing platforms such as Zoom, Google Meet and Microsoft Teams for bilateral decision-making gatherings, diplomatic meetings, and conferences. Furthermore, social media platforms are increasingly being appropriated by embassies, foreign affairs ministries and other government officials to influence public opinion, manufacturing consent and dissent and enhancing a country’s image. Twitter has become a key tool used by diplomatic missions as well as governments across the world to communicate with local citizens and foreign nationals.

Few countries in Africa serve as an interesting research laboratory to examine how the embassies of two global superpowers – US and China – engage in digital public diplomacy on Twitter than Zimbabwe. The country has been going through cycles of protracted socio-political and economic crises ever since the turn of the century when it embarked on the controversial Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) in 2000.

This unexpected move to redistribute white-owned land without compensation led to disruptive diplomatic tensions between Zimbabwe and the United Kingdom (UK), the Europe Union (EU), and the United States (US). The EU reacted by imposing targeted sanctions on Harare. The US followed suit by promulgating the Zimbabwe Democracy and Recovery Act (ZDERA) in 2001.

Demonstrators hold placards as they chant slogans and wave Zimbabwe’s national flags during a rally to denounce US and EU economic sanctions against Zimbabwe at the National Stadium, in the capital, Harare, in 2019. Photo: Jekesai NJIKIZANA / AFP

Although there are conflicting views on the actual import of the Act from both the Zimbabwean and American governments, the Act represented targeted sanctions on the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and its political and economic allies. From the perspective of the Americans, the Act was meant to support the people of Zimbabwe in their struggle to effect peaceful, democratic change, achieve broad-based and equitable economic growth, and restore the rule of law. ZANU-PF saw this as part of a foreign-sponsored regime change agenda aimed at propping up the opposition fronted by the Movement of Democratic Change (MDC).

With this diplomatic tiff between Harare and the West, dormant relations with China, which dated back to the liberation struggle, were swiftly rekindled. The Zimbabwean government came up with the Look East Policy (LEP) in search of partnerships with rising economies from the East such as China, Russia, Iran, Indonesia, Singapore, and Ukraine. Because LEP was an oral secret public policy, there is a general belief that it was designed to benefit the political elite in Harare who had a vested interest in a close economic and political relationship with China and other countries from the East at the cost of the interests of the people of Zimbabwe.

The pronunciation of this policy meant that the US and China were now pitted against each other regarding their foreign policy thrusts toward Zimbabwe. With China in a cozy relationship with the ZANU-PF government, the West was open in its embrace and support of the MDC. Resultantly, some kind of “cold war” between the US and Chinese sides has characterised the country’s bilateral relations over the past two decades.

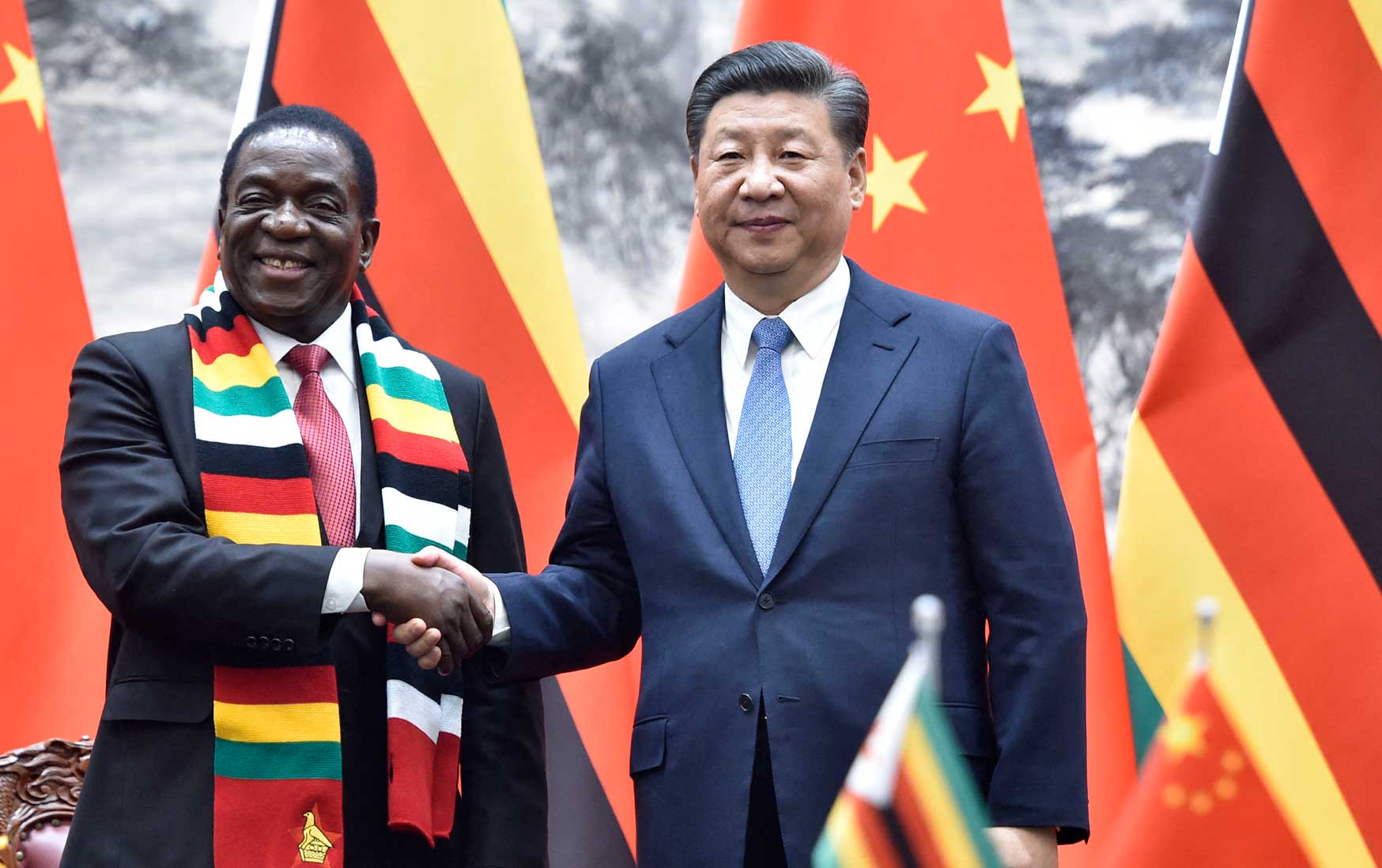

Noteworthy to highlight with the military coup that ousted Robert Mugabe from the political cockpit after 37 years of rule, the Second Republic under the leadership of Emmerson Mnangagwa adopted a new foreign policy thrust of affirmation, engagement, and re-engagement. This multi-pronged foreign policy approach was different from Mugabe’s policy which over-emphasised principles such as emancipation, self-determination, support for liberation movements, safeguarding the country’s sovereignty, and the protection of its prestige and image, promotion of the principle of equality among nations, and belief in non-discrimination. Mnangagwa’s foreign policy approach sought to restore Zimbabwe to the family of nations after decades of splendid isolation. On paper, it represented a total break from the antagonistic relationship forged by Mugabe’s regime for two decades.

Zimbabwe’s President Emmerson Mnangagwa shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping as they pose for the media after a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on April 3, 2018. Photo: Parker Song / POOL / AFP

It is within this context that I embarked on a study to understand how the Chinese and American embassies deploy Twitter to advance their foreign policy goals in Zimbabwe. Using the case study of the US (which has a diplomatic standoff with Zimbabwe) and China (which is often described by Zimbabwean authorities as an “all-weather friend”), this study sought to investigate how their embassies used Twitter to promote their foreign policy goals. The study looked at the posting behaviours, thematic issues, and responses of these embassies to controversial topics related to their foreign policies.

The choice of these two embassies was motivated by the fact that both countries have different bilateral relationships with Zimbabwe. The key research questions were: How are the Chinese and US Embassies in Zimbabwe using Twitter to promote their foreign policy goals? What are the main thematic issues that both embassies are concerned about in the host country? How do the two embassies engage with local citizens and foreign nationals on Twitter?

Deploying virtual ethnography and qualitative content analysis, I monitored the Twitter handles of the Chinese (@ChineseZimbabwe) and American (@USEmbZim) embassies. I also followed and monitored the activities of the ambassadors (former US ambassador Brian Nichols (@WHAAsstSecty) and Guo Shaochun (@China_Amb_Zim) of both countries to Zimbabwe, government officials (Emmerson Mnangagwa, president of Zimbabwe (@edmnangagwa), Frederick M.M. Shava (@ShavaHon), Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Prof Mthuli Ncube, Minister of Finance (@MthuliNcube), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (@MoFA_ZW), and some of the most prominent staff working for these embassies. The American Twitter handle clearly articulates the country’s foreign policy thrust in Zimbabwe, which is to promote active engagement and partnership with Zimbabweans to build a better future. The Chinese Twitter handle has no description of the embassy’s foreign policy remit in Zimbabwe.

Both embassies have a significant following on Twitter. The Chinese embassy in Zimbabwe (@ChineseZimbabwe) has approximately 13,800. It only follows 140 accounts, mostly Nick Mangwana (@nickmangwana), Emmerson Mnangagwa (President of Zimbabwe), the Russian embassy in Zimbabwe, the Chinese ambassador to Zimbabwe, Sunday Mail (state-owned weekly newspaper), and Global Times (Chinese state-owned media), amongst others. It was opened in September 2018, a few months after Mnangagwa sanitised his military-assisted coup via controversial elections held in July 2018. China and the UK are generally believed to have played a “behind the scenes” role in the successful execution of the November 2017 coup.

The US embassy Twitter handle was created in July 2009, soon after the formation of the government of National Unity (GNU) and one month before the launch of 3G technology in Zimbabwe. It has 358,300 followers and follows about 1,412 accounts.

Both embassies run very vibrant pages characterised by regular posts, retweets and hashtagging. It was observed that both accounts rarely respond to comments by their followers. Both used their accounts to broadcast their foreign policy messages.

The Chinese Twitter handle is very vocal about denouncing the so-called “illegal sanctions” the West imposed on Harare in the early 2000s. In one of the tweets, the handle described the US as the “United States of American Sanctions”. Occasionally, the US embassy responds to this narrative by highlighting that targeted sanctions were imposed after the breakdown of the rule of law and human rights violations.

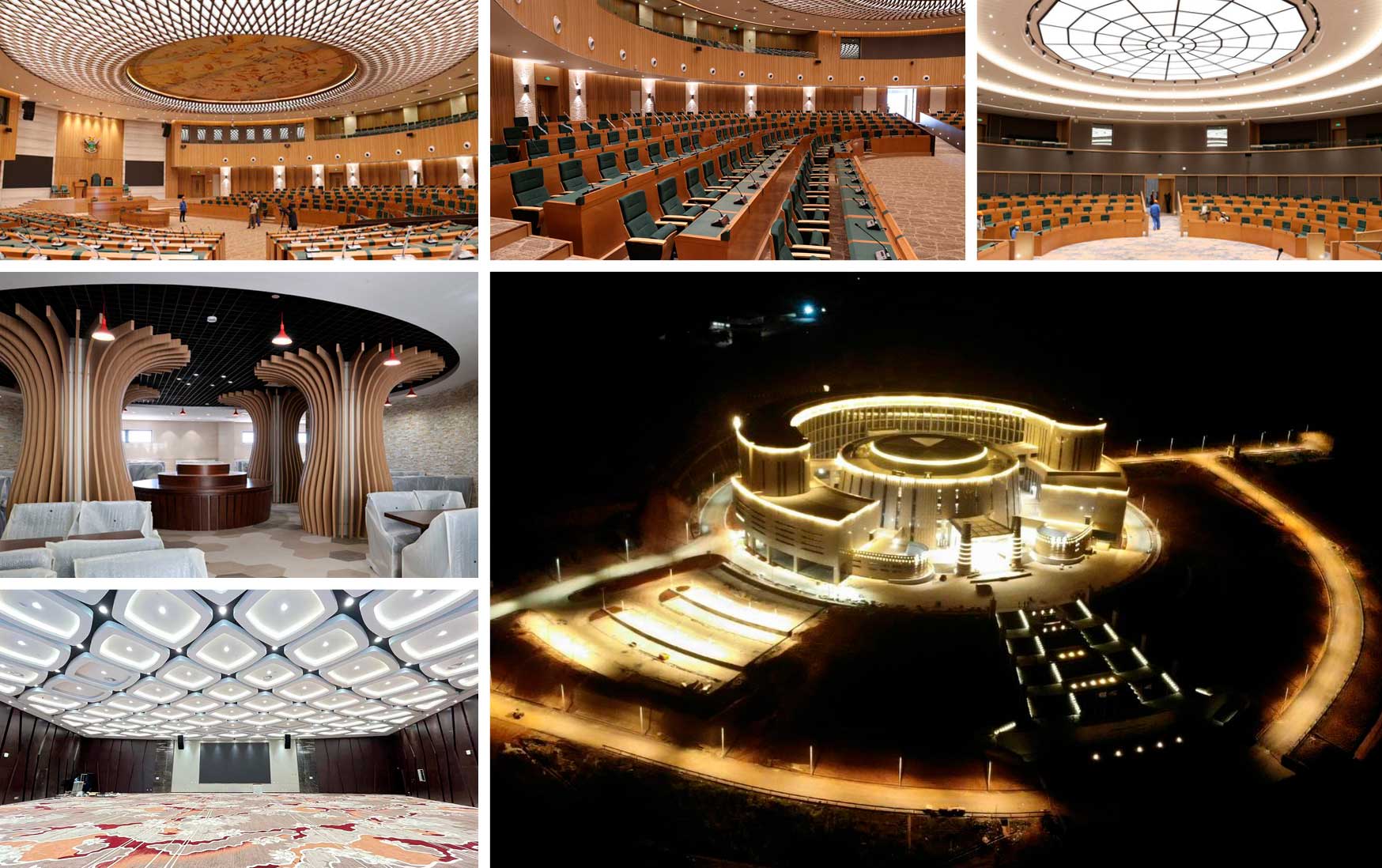

The new Chinese-funded, six-story, parliament building in Mount Hampden, 25 km northwest of the capital, Harare. Photos: @newparl_project and @DeptCommsZW

Observations on both handles revealed that administrators occasionally used their platforms to attack, respond and outcompete each other. The Chinese embassy used videos and testimonials to showcase the success of their non-interference economic diplomacy approach in Zimbabwe. In these videos and testimonials, Chinese companies are presented as job creators, law-abiding corporate citizens, and socially responsive actors. In some cases, Zimbabwean citizens are filmed defending the economic activities of Chinese firms. This is in contrast to a popular derogative term for Chinese goods that are often referred to as ‘Zheng Zhong’ (meaning cheaper and low-quality goods). Chinese companies have also been arraigned before the courts for violation of the Labour Act.

The Chinese embassy used its handle to attack the US’s unipolar approach to international relations, exceptionalism, and bullying tactics. For their part, the US embassy has used its handle to influence public opinion in Zimbabwe by profiling and promoting social and development activities spearheaded by the United States Development Agency (USAID). The Twitter account sought to show the country’s unwavering relations with the Zimbabwean people since 1980, highlighting areas where the US helped during droughts, famine, and economic crises.

In line with the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001 (ZDERA), the US embassy tweets revealed that they use trusted non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to support Zimbabweans. This suggests that the US government avoids directly supporting the government by channeling aid through non-state actors. The Chinese embassy also boasted of investing large sums of money into infrastructural developments, manufacturing, mining, and agriculture (especially tobacco and cotton). They regularly tweet about the construction of the new parliament building in Mount Hampden, described in the media as a “Chinese gift” to the Zimbabwean people.

The study also noted that the US embassy only retweeted American-related stories published by the State Department, US Africa Media Hub, and USAID. For their part, the Chinese embassy commented and retweeted on stories focusing on investments by their governments and companies operating in Zimbabwe. They also retweeted stories about Chinese investments covered by state-owned media and tweeted by verified Zimbabwean government officials’ Twitter handles.

The Chinese handle regularly accused the US of being the chief purveyor of disinformation and propaganda. In one of the tweets, it accused America of genocide and war crimes. It also accused the US of orchestrating smear campaigns targeted at development-supporting Chinese investments. The handle also accused America of attempting to sow seeds of disunity and mistrust between the Chinese and the people of Zimbabwe.

The Chinese handle was also articulate about the issue of vaccine diplomacy, highlighting the number of doses donated to Zimbabwe. Consistent with studies conducted elsewhere, this study found that both countries were using Twitter predominantly as one-way information dissemination as opposed to engaging the audience in a two-way flow of communication. Although the US embassy recently introduced Twitter Spaces as interactive spaces to discuss pertinent issues, these are still moderated by gatekeepers.

Overall, from this exploratory study, it is clear that both embassies are using their handles to influence public opinion in Zimbabwe. They are also using the platform for enhancing their country’s image in the eyes of Zimbabwean citizens. They are also using Twitter as a battleground to push their political and commercial diplomatic interests.

[activecampaign form=1]